MAD Men

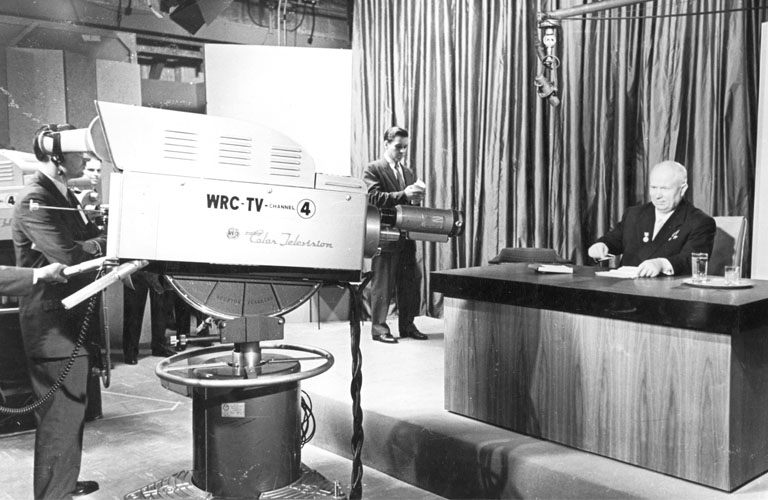

Direct messaging: John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev behind the mike.

Direct messaging: John F. Kennedy and Nikita Khrushchev behind the mike.Credits: picture alliance / dpa | Robert Knudsen / White House / H, IMAGO/agefotostock

As fears of nuclear war increase, it’s worth looking at the Cuban Missile Crisis for historical insight

In the contemporary discourse on Putin’s war in Ukraine, experts have drawn comparisons to what they consider comparable historical events. At the same time, however, a number of key historical incidents have been disregarded. For example, there is a passionate argument currently underway about whether the events of February 2022 are more like those of July 1914 or those of September 1938. People are also arguing about which label better suits the current leaders in Berlin: Are they sleepwalkers or appeasers? In contrast to these robust disputes, there is one historical event we’ve heard barely a peep about, namely the first successful atomic bomb test in the New Mexico desert in the summer of 1945. There would be no turning back when, four years later, the Soviet Union detonated a nuclear device of its own. Since that day, all forms of global political strategy and maneuvering have been shadowed by a fundamentally new fact: from that moment on, any war between great powers carried the risk of the complete annihilation of all peoples involved as well as the extensive devastation of the planet. With this in mind, it is fully understandable that a subcutaneous fear of the atom bomb is emerging again today. Unfortunately, however, the debate about how these fears were managed in the past – as well as an in-depth discussion about the conclusions we can draw from related historical events – is being pursued to a far lesser degree than would benefit us now.

It is also understandable that the current state of affairs in Ukraine would bring to mind the Cuban Missile Crisis of October 1962, in which the US and USSR clashed over the stationing of Soviet nuclear missiles in the Caribbean. The standoff between these two nations became so explosive that nuclear war was averted only at the very last moment and with a great deal of luck. One might argue today, of course, that Havana is not Kyiv. And yet, this near-war of yesterday says more about the current war in Ukraine than most other milestones from years past. The fact that nuclear weapons are rather blunt military tools whose immense destructive power makes them entirely unsuitable for actual warfare is quite evident. The other side of the coin, however, is a highly volatile one, namely the relentless struggle to sharpen these weapons – or at least gain some kind of added political value from them – in times of peace. It is clear that Putin is playing precisely this game at the moment, especially in his repeated threats to actually use nuclear weapons. The idea behind this approach is both archaic and momentous, and involves a great power coming under the suspicion of not being able to draw any advantage from the most powerful instrument in its arsenal. For this nation to have remained a great power for so long, it has had to master the craft of intimidation and blackmail. If it ever failed to do so, it would face a forced relegation to the sidelines of world politics. Casting an air of mystery over one’s intentions, sowing mistrust, exploiting uncertainty, blurring the line between a bluff and risky va banque and wearing down one’s opponents: such have been the cornerstones of Russian policy for decades and still are today. An approach like this falls under the harmless name of deterrence; fear is its driving force, and its goal is to scare others to such an extent that one can impose one’s will on them even under the most adverse conditions. Indeed, this has been the historical modus operandi on both sides.

John F. Kennedy, a US president much lauded for his cool intellect, indulged in this logic several times in 1962. “Khrushchev must not be certain that, where its vital interests are threatened, the US will never strike first. In some circumstances we might have to take the initiative.” It is almost unnecessary to note that it remains unclear what was meant by “vital interests” or “some circumstances.” JFK continued: “We will not needlessly risk world-wide nuclear war, […] but neither will we shrink from that risk when it must be faced. I have directed the Armed Forces to prepare for any eventualities.” Conversely, the term “needlessly” was likely meant to imply that it might well be necessary to press the red button at the appropriate moment. The Kremlin pretended to be unimpressed and justified its shipment of 36 medium-range nuclear missiles to Cuba by flashing a further trump card: they argued that since the Americans had been positioning similar-range missiles in Turkey – that is, in the direct vicinity of the USSR – for years, it was high time to give the US a taste of its own medicine in an equivalent location.

Such exaggerated displays ultimately achieved a state of affairs once described by the physicist Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker as the following: “The only way big bombs can fulfill their purpose of safeguarding peace and freedom is if they’re never used. In the same vein, however, they will not be able to fulfill their purpose if everyone knows they will never be used. This is precisely why there is a danger that one day they actually will be used.” An equally illuminating account might read as follows: the likelihood that things will escalate to that ultimate point increases proportionally with the duration and intensity of each confrontation. This is the case for one simple reason, which is that each crisis has its own dynamic; that is to say, each crisis causes upheavals that no one intended at the outset and hardly anyone knows know how to contain in the end. For this reason, it would be careless to dismiss the poker game being played today with nuclear weapons as some kind of mere scaremongering. Such games can come back to haunt their originators at any time. In other words, deterrence is founded on preconditions that no one can control.

That being said, it would have been reasonable to expect Moscow to keep still in the early 1960s. Back then, the West was in a vastly superior position than its adversary in all matters relating to nuclear weapons. The US possessed five-and-a-half times the number of intercontinental missiles (230 to 42) plus, in contrast to US solid-fuel missiles, the Soviet models were only capable of becoming operational after hours of refueling and therefore had only a limited degree of suitability for war. With regard to nuclear warheads, the Soviets were outnumbered by the US, UK and France by a ratio of 1:17 (300 to 5000), and the US had more than 1,400 long-range bombers compared to only 155 aircraft bearing the Red Star. And yet, in spite of this inferior position, Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev chose to go on the offensive rather than submit to such a grotesque dominance. He put on a highly intimidating performance designed to make sure that no one got the impression he was afraid of the US. According to his logic, neutralizing the long arms of the US meant showing the world the uselessness of that nation’s superior strength. As Khrushchev later explained to his inner circle, all of these moves – feigning unpredictability, making pinpricks and provoking resentment – were part of the game: “One must not shy away from driving others into a state of rage. Otherwise we’ll never get anywhere. […] Anyone with weak nerves will be pushed up against the wall.”

No matter what kind of questionable motives played a role in launching this arm-wrestling match, the consequences of the struggle would turn out to be far more serious. Indeed, as soon as both sides decided in favor of a test of strength rather than diplomatic rapprochement, the result was a mutual acceptance that everything willy-nilly was possible. When a US reconnaissance plane was shot down by Soviet anti-aircraft fire over Cuba, the White House assumed this was a deliberate escalation and began to prepare an appropriate response – not knowing that that the local commander had ignored a vague ban on firing issued by the Kremlin. When a US military plane veered off course due to problems with its navigation system and ended up cruising through Soviet airspace for a seemingly never-ending amount of time, Defense Secretary Robert McNamara lost his cool, exclaiming: “This means war with the Soviet Union!” And he had every reason to fear this was the case. No one knew why two Air Force interceptors, armed with nuclear-capable air-to-air missiles, had been sent up to support the stray planes, or what directives the pilots were given or why it took an hour and a half for the Pentagon to be informed of the events. And so the confrontations continued, including a number of incidents on the high seas in which Soviet submarines were forced to surface – and where it was left solely to the submarine captain’s discretion whether to launch nuclear torpedoes at their pursuers or turn tail. To put it succinctly, in such situations, small things can throw everything off kilter and decide whether millions will live or die. For this reason, Kennedy soon deleted the grandiose concept of crisis management from his vocabulary. The president pointed out that no matter what a commander orders in extreme situations, his influence is nevertheless subject to strict limits if and when somewhere at the end of the chain of command there’s “some son-of-a-bitch who doesn’t get the word.”

So far, there have been no such escalations in Ukraine. Still, there’s no reason to glean comfort from this in any way. After all, the crude verbal attacks issued by Putin and his camarilla – including calls for the “denazification” of Ukraine and threatening rapid counterattacks in the event of an unspecified Western interference – only add emotional fuel to the fire of unrestrained behavior, especially in light of an entire array of potential coincidences, misperceptions and acts of negligence. The Cuban Missile Crisis, at any rate, teaches us that overreactions are part and parcel of the power struggle between nuclear powers. Immediately after the US discovered that Soviet medium-range missiles had been stationed on Cuba, Florida began to resemble an army encampment. The British consul in Miami at the time said that it reminded him of the situation in southern England in June 1944 and the final days before the landing in Normandy. Other observers argued that the peninsula was likely to sink into the sea under the weight of all the military equipment massing there. Almost 600 tactical fighter-bombers had been set up across the state’s airfields, equipped with fuel, bombs and onboard ammunition for thousands of attacks; the plan was to fly 1,190 sorties on the very first day of a potential war against Cuba. Under Army Command, eight divisions with a total of 120,000 soldiers and the largest mobilized contingent of paratroopers since 1944 were preparing for an amphibious landing east of Havana (just for comparison, 150,000 troops had been dropped at Normandy). The Navy had 180 ships on offer, including eight aircraft carriers and 26 destroyers. These were jaw-dropping numbers by any measure.

Still, the objective of this massive deployment wasn’t a military one. It was about politics, and especially about the psychology of power. Those three dozen Soviet missiles in Cuba hadn’t changed anything about the true balance of power between the two superpowers, the US president and his most important advisors agreed. What was at stake here – much more importantly – was image and prestige. There was no way the US was going to give the impression it was shrinking away from a small war just because of the risk of a big one; in other words, the US had no intention of committing suicide out of fear of its own death, as one common metaphor expressed it at the time. Strictly speaking, anyone displaying any type of weakness in these and similar situations will never be able to rid themselves of the stench.

In this respect, the 1962 crisis was less about what to do with Cuba and much more to do with the future of the US. In effect, it was a test run to show existing and potential rivals that they had no chance in a global competition with the US. It was also designed to prove Washington’s will to power. The brash performance of the US in the Caribbean was aimed at putting the Soviets in a position from which they could only extricate themselves by means of an all-out war, while at the same time preventing them from taking this step by displaying the Washington’s own superiority. Confident in their power, Kennedy’s advisors called for a swift invasion of Cuba without any thought of the incalculable consequences. Drawing on the words of historian Barbara Tuchman, it was a quest for credibility so importunate as to border on self-hypnosis.

We hear a distant echo of this approach emanating from Ukraine today. Putin’s threats with regard to nuclear bombs accentuate his ruthlessness, and the extensive arms deliveries from the US – which are practical, effective and intended to strengthen a nation directly under attack – point to a world beyond this particular stage. These moves simultaneously underscore a much broader aim and are directed primarily at China. They are intended as a warning not to challenge the US, no matter when or where. Unfortunately, as we’ve seen, this is precisely where the most severe danger lurks, that is, in a policy that sees the use of military force not as one means among many, but as the main instrument for asserting interests and as the most important measure of national standing. In the case of China, however – and this cannot be emphasized enough – the West is dealing with an adversary who, unlike Putin, has no need to feign strength as a way to conceal their weaknesses.

It would appear that Vladimir Putin continues to be fully beholden to the logic of 1962. Only he knows what kind of devil prompted him to make the decision to attack a neighboring country. It is unlikely that he saw NATO’s eastward expansion as representing a serious shift in the material balance of power. Something else must have presented itself to him as being more threatening than military hardware; perhaps it was the impression that Russia had maneuvered itself into a position in which it felt it had no means to counter this projection of power and thus found itself standing there like a pawn of the West. This is the point at which, at the latest, Khrushchev would have entered the scene with his familiar recipe of making the Americans look like paper tigers. Perhaps the idea of putting Ukraine to the test was simply too tempting for Putin, not least because there’s no way to counter Russia’s escalation dominance in those regions near its border, no matter what kind of equipment is supplied to Ukraine by third parties. Ultimately, the posturing is all about symbolic capital, that is, about revitalizing the aura of a faded great power. With its own stated peaceful intentions, NATO can run up against this posturing all it wants. For Putin, the only thing that matters is that Russia’s is was at stake. This was precisely the case during the Cuban Missile Crisis, as well, when overreaction was thought to be the only appropriate response.

On the one hand, in October 1962, all signs pointed to a coming storm. Irrespective of the tight spot both governments found themselves in, it was Kennedy who came under massive pressure from the public. Even without help from today’s social media, which often acts as an accelerant to public opinion, a general furor spread; people argued that it wasn’t possible to reach any kind of understanding with a dictator, and that Khrushchev and his foreign minister Andrei Gromyko should not only be punished for engaging in blackmail but also expected to atone for their brazen lies to the president in personal talks and to the whole world at the United Nations. Politicians who got caught up in this maelstrom were accused of lacking leadership and being cowardly, indecisive, wavering, timid and cautious – with all allegations varying in tone and degree – such that they were forced to reckon with the potential end of their careers. The parallels to our present day need no explication.

On the other hand, Kennedy knew that the fixation on purely military measures would only lead to a dead end: “It isn’t the first step that concerns me, but both sides escalating to the fourth and fifth step – and we don’t go to the sixth because there is no one around to do so. We must remind ourselves we are embarking on a very hazardous course.” In other words, it was time to do away with the rhetoric, refrain from making any high-sounding gestures and play for time. At that point, the president began establishing top-secret contacts to the opposing side. It is impossible to say how far Kennedy would have been willing to go; the pressure to order a strike was immense. Fortunately for him as well as for all of us, his adversary took away any need for him to make a decision: only hours before the Kremlin was to be presented with a face-saving offer – which stated that Washington would renounce an invasion of Cuba in return for the withdrawal of missiles there and possibly dismantle its own missiles in Turkey within six months – Nikita Khrushchev pulled the emergency brake. Shortly thereafter, he informed the Politburo of his decision to abandon the missile base in Cuba even without a material quid pro quo: “Any fool can start a war, “he said, “and once he’s done so, even the wisest of men are helpless to stop it – especially if it’s a nuclear war.”

What can we deduce from all of this? First of all, it would be naïve to hope that today’s arsonist will transform into a fireman, as Khrushchev did in 1962. Putin is no Khrushchev and, unlike his predecessor, seems to overestimate himself immeasurably. This makes it all the more imperative to keep as many communication channels open as possible – not in spite of the fact that the prospects for compromise are so bleak but precisely because of it. This is certain to be an arduous path and possibly the rockiest one to take. But the alternative – insisting on absolutist demands and declaiming in public what everybody already knows – would achieve nothing other than a further hardening of the fronts.

The Cuban Missile Crisis is also worth looking at with regard to the future security order in Europe and beyond. If there were but one timeless experience we can draw on from the early 1960s, it’s this: more nuclear weapons and more nuclear deterrence solve no problems, they are the problem. To ignore this insight would amount to sleepwalking through history.

The article originally appeared in the Blätter for deutsche and internationale Politik.

Historian Bernd Greiner is professor emeritus at the University of Hamburg. He is a founding chairman of the Berlin Center for Cold War Studies.