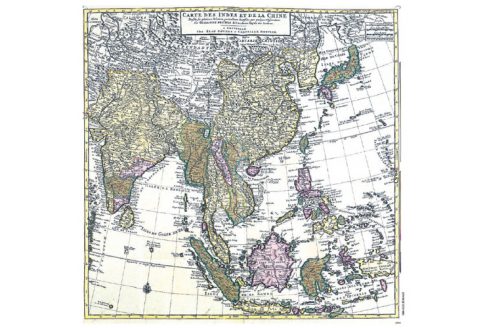

World powers are scrambling for influence over Asian maritime routes

Security alignments in the Asia-Pacific are quickly hardening in response to China’s rise and regional assertiveness.

These realignments have led to the formation of the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, or simply the Quad, which comprises the United States, its two close allies Australia and Japan, and India. The Trump administration’s endorsement of the term “Indo-Pacific” gives these alignments a maritime focus on the sea lanes traversing the Western Pacific, South China Sea and Indian Ocean.

The Quad is not a formal military alliance, but each of its four members is pushing back against a rising China that has been assertive in pursuing its interests at their expense. Last year, for example, Indian and Chinese military forces were involved in a two-month confrontation on the Doklam Plateau, a tri-border area shared by China, India and Bhutan. In February, satellite images revealed that both sides were building up defenses, with China’s efforts far outweighing India’s.

Japan faces constant challenges by Chinese naval and air forces operating in waters around the Japanese-administered Senkaku Islands. In January alone, Chinese Coast Guard vessels intruded twice into Japan’s territorial sea while a Chinese frigate and a submerged Shang-class nuclear attack submarine entered Japan’s contiguous zone.

Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has been instrumental in knitting closer political ties with India and enhanced defense ties with Australia.

Australia, which is not geographically proximate to China, faces challenges of a different sort: Chinese interference in its domestic affairs. The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) stated in its 2016– 17 annual report that they had “identified foreign powers clandestinely seeking to shape the opinions of members of the Australian public, media organizations and government officials in order to advance their country’s own political objectives. Ethnic and religious communities in Australia were also the subject of covert influence operations designed to diminish their criticism of foreign governments.”

In late January, it was reported that ASIO listed China as an “extreme threat,” the highest level on a secret country-by-country counter-intelligence index.

ASIO’s assessment was backed by widespread media reports of Chinese influence operations in Australia, including cash donations to political parties. The United Front Work Department – an organ of the Chinese Communist Party – and Chinese businessmen were identified as key actors in activities designed to influence Australian politicians, the Chinese community and Chinese-language media.

In a high-profile case in 2017, a Labor Party frontbencher, Senator Sam Dastyari, resigned from parliament after it was revealed that he had accepted cash donations from a Chinese businessman, reportedly in return for supporting China’s territorial claims in the South China Sea.

On Nov. 23, 2017, the Australian government released its Foreign Policy White Paper. This document, without specifically naming China, highlighted the challenge to US primacy “by other powers” that openly contested the principles and values on which international order is based. The white paper assessed that China’s power and influence will grow to match, “and in some cases exceed,” that of the United States in the Indo-Pacific. A Chinese spokesperson called the white paper “irresponsible.”

The white paper depicted territorial disputes in the South China Sea as a “major fault line” in the region, noting that Australia was “particularly concerned by the unprecedented pace and scale of China’s activities… (and) opposes the use of disputed features and artificial structures in the South China Sea for military purposes.” It also stressed the importance of US leadership and participation in a rules-based international order. At a time of growing strategic uncertainty, Australia has picked up the strategic slack and engaged more with like-minded democracies in the Indo-Pacific. Australian Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull and Prime Minister Abe have stepped up defense cooperation between their two countries.

The United States has long-standing concerns about freedom of navigation by naval vessels and military aircraft over the South China Sea. In May 2017, President Donald Trump approved the defense department’s plan for a full-year regular schedule of freedom-of-navigation operations (FONOPs). As these are officially considered routine operations, they are not widely publicized.

China, however, publicly criticizes FONOPs as a threat to its security and a violation of its sovereignty. The US Navy reportedly conducted four FONOPs in the South China Sea in 2017 and one in January of this year.

At the end of his first year in office, Trump approved a new US National Security Strategy (NSS) that singled out China and Russia as strategic competitors. With respect to the Indo-Pacific region, the NSS focused almost entirely on the maritime domain, freedom of navigation, and free and reciprocal trade.

The NSS bluntly declared: “China is using economic inducements and penalties, influence operations, and implied military threats to persuade other states to heed its political and security agenda. China’s infrastructure investments and trade strategies reinforce its geopolitical aspirations.”

References in the NSS to US support for high-quality infrastructure promoting economic growth indicates that Washington will push back against China’s Belt and Road Initiative and offer regional states an alternate source of funding.

Shortly after the release of the NSS, the Pentagon issued a new US National Defense Strategy (NDS) that highlighted strategic competition among the major powers as the primary concern of the United States. China and Russia were explicitly identified as revisionist powers seeking to overly influence other countries economic, diplomatic and security decisions.

With respect to the Indo-Pacific region, the NDS identified China as a strategic competitor that sought to undermine America’s position in the region. The NDS posited three main “lines of effort” to achieve the objective of a free and open Indo-Pacific region. The NDS promoted a US-led “networked security architecture” consisting of allies and partners – including Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore – to ensure regional stability and free access to the maritime commons in the Indo- Pacific.

The Quad is a work in progress, the formation of which was spurred by China’s creeping militarization of its islands in the South China Sea. Prime Minister Abe has proposed a possible agenda including the provision of aid, infrastructure and maritime security to assist regional states in resisting Chinese dominance.

The first meeting of Quad naval chiefs in New Delhi in January of this year is a harbinger of the new realignment across the Indo- Pacific to push back against an assertive China.

CARLYLE THAYER

is emeritus professor at The University of New South Wales at the Australian Defense Force Academy, Canberra.