Cable news

Credit: Shutterstock/piscari

Credit: Shutterstock/piscari Underwater infrastructure is the West’s next great security risk

Europe is increasingly in danger of being caught between fronts. Russia and China are pursuing their confrontational power politics ever more aggressively, not only using Europe’s continued demands for energy, critical raw materials and rare earths as leverage, but also attempting to gain control over data flows and communication channels.

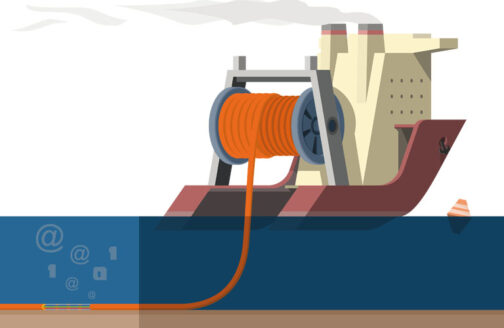

Access to data and the ability to protect its integrity are essential to our security and prosperity. Data is arguably the most important strategic asset of our time. We tend to think that our data is held in the cloud and that everything is interconnected by space, but that is not entirely true. Indeed, our data is carried by underwater cables on the ocean floor – in some cases up to 4000 meters deep. The digital age is really a cable age.

The backbone of the global economy and the vast bulk of agency intelligence worldwide travel along the same cables that carry our emails and Netflix shows. More than 95 percent of international data traffic is based on a global network of physical, submarine cables – each not much wider than a garden hose. And then there’s the new underwater energy infrastructure used to export solar power and hydrogen. Yet Europe has left itself vulnerable in doing little to protect this increasingly important undersea technology.

These vulnerabilities were drilled home last September with the explosions that occurred on the Nord Stream gas pipeline in the Baltic Sea. It is clear that the incidents were deliberate, and that there are powers with an interest, and apparently the means, to carry out targeted attacks on the backbone of our energy supply. But almost five months later, official investigators are still reluctant to point the finger at possible perpetrators. Governments appeared unfazed by the fact that Europeans have the right to know whom they should thank for the full extent of the energy crisis. The sabotage at sea remains a mystery, although widespread speculation continues to blame the Russian Federation for the blasts. Despite the uncertainty, the attack has only heightened concerns about the threat to underwater infrastructure. It has also served as reminder to us Europeans of the vulnerability of our energy supplies. What will we do if the next attack targets a large offshore wind farm or the North Sea pipeline from Norway, which is so important in the current crisis? The concerns are justified, but fear does not help in this situation. This much is clear: We must do a better job at protecting our critical infrastructure – and defend it, if necessary.

In addition to the risk of sabotage and attacks, the question of submarine cable control has become a burning issue for Europe. The growing amount of data passing through the cables encourages third countries, especially those not sympathetic to the West, to spy on or sabotage them. We are facing a paradigm shift with regard to how the digital sovereignty and strategic autonomy repeatedly championed by Brussels can actually be realized.

Trans-Atlantic data traffic doubles every two years, while the average age of European submarine cable systems is almost 20 years. At the same time, the laying and maintenance of submarine cables is becoming increasingly expensive, and a growing number of non-European players are wrangling into this vital strategic realm. This leads to the formation of sometimes confusing cable consortia with different owners and specific interests – and state actors, including those from China, are also involved.

Once upon a time, it was the Europeans who drove the interconnectedness of the world forward. The first ocean cable was laid between the United Kingdom and France in 1850. The first fiberoptic cable heralded a new era in trans-Atlantic communications in 1988, as a joint project of the then partly state-owned telecommunications companies AT&T, France Télécom and British Telecom.

Today, there are only a few European providers that themselves lay cables through the oceans. One of them is the Finnish company Nokia, which has repeatedly considered selling this business. As a result, there is growing concern that Europe will permanently lose its technological prowess in this field – and thereby forfeit its sovereignty.

As Russia and China continue to vie for geopolitical advantage through their attempts to control the flow of data and communications, Europe finds itself tussling on at least two fronts. The Indian Institute for Peace and Conflict Studies and the Asia Center in Leiden, Netherlands, estimate that China’s share of global submarine cables will reach 20 percent between 2025 and 2030. Another challenge for European policymakers and local companies is to stand up to the growing monopoly of American technology giants, such as Google, Apple, Facebook, Amazon and Microsoft, as well as Chinese competitors, to assert their own sovereign rights. Private operators already control more than half of the submarine cable bandwidth. Additional risks to operational security are posed by the fact that an increasing number of cable operators are using remote management systems for their networks as a way of reducing personnel costs. However, these systems are poorly secured, exposing submarine cables to cybersecurity risks.

Unlike Russia and China, Europe has been less vigilant about who makes or installs its cables and is more dependent on cables across oceans. This makes Europe more vulnerable. The EU must expand its own capacities and lay more submarine cables, as well as replace outdated ones, to reduce its exposure to attacks and boost its independence.

Improving public tenders and the tendering principle for the construction and/or maintenance of critical infrastructure – both below and above the surface of the ocean – would help strengthen digital sovereignty and correct home-grown regulatory and structural errors. The same can be said about excluding certain states that pose a security risk. We will continue to remain vulnerable as long as the best-bidder principle applies to tenders and non-European competitors. Sometimes even state-subsidized providers outbid trustworthy European security solutions, which are then applied in the area of critical infrastructure.

And it is especially here, in the area of critical infrastructure, that we need to refocus on Europe and rely solely on local solutions and operators to protect our own interests. At the same time, protection concepts should already be implemented when laying submarine cables and pipelines – and landing stations should be directly integrated into this planning.

Likewise, a military response is needed: Unlike during the Cold War, NATO has few frigates designed for anti-submarine warfare, let alone submarines capable of performing maintenance on strategically important underwater cables at greater depths. China and Russia, meanwhile, have upgraded and specialized their navies for such maritime operations.

NATO and individual partners, such as France and the UK, have now begun to close this open flank. A new NATO Atlantic Command based in Norfolk, Virginia, has been tasked with protecting the transport and communication routes between North America and Europe. In turn, however, it is now essential to establish a fleet suited to the task of guaranteeing this security.

The commissioning of the first ship in the British Navy to protect submarine cables is an initial step, and a second ship is planned. But two ships alone will hardly be able to protect the more than 400 submarine cables in use worldwide, that is, unless other NATO partners, such as Germany, join in, and especially since at least 45 more ocean cables are to be laid by 2025. In addition, it is crucial to work with the telecom companies that have the equipment to monitor and control this large area.

Furthermore, it is not only submarine cables that are of great strategic importance for Europe’s future as an economic power, as the world produces more and more data: Analysts predict that global data volume will increase to a whopping 175 zettabytes – that’s a 175 with 21 zeros! – by 2025. At the same time, the global demand for energy is also rising, especially due to advancing digitalization and ever-larger data centers. According to the US Energy Information Administration (EIA), global energy consumption is increasing by an average of up to 2 percent annually. Energy security is also currently the main factor driving the energy transition, as countries look to energy technologies and renewables as a solution to the quandary of how to free themselves from their dependence on Russian oil and gas. More underwater infrastructure is thus needed to transport renewable electricity and, in the future, hydrogen via pipelines.

The task of protecting this critical infrastructure has become increasingly urgent and requires a new security and resilience strategy for Europe and beyond. The high vulnerability of underwater infrastructure and its key geostrategic role is not up for debate – and has become yet another realm of contention between the great powers of the East and West. Europe cannot afford to fall asleep at the wheel. It must continue to learn to assert itself on the global stage.

The flagship projects associated with the Global Gateway Initiative are the appropriate next steps in Europe’s efforts to express stronger global leadership in the future. The initiative aims to offer developing countries an alternative to the strategic largesse inherent in China’s Belt and Road Initiative, by means of which Beijing demonstrates its power along strategic trade routes by developing ports, energy projects and telecommunications networks.

It is precisely the security of these data networks that looms so large in the coming years. The wars of the future will no doubt include conflicts over undersea data cables and energy transport structures. Europe must prove it can nip this crisis in the bud and future-proof itself in ways that allow it to effectively tackle long-term challenges.

Oliver Rolofs is a strategic security and communications expert and founder of COMMVISORY. He was previously the head of communications at the Munich Security Conference, where he established the Cybersecurity and Energy Security Program.