Global arms sales have grown for the third year in a row with Russia crowding out the UK for second place

The difference in numbers is striking. Whereas $7.87 billion was spent on the 16 peacekeeping operations organized by the United Nations, global arms sales reached almost $400 billion. For the third year in a row, the United States along with Russia, China, Great Britain, France and Germany earned almost fifty times more in arms revenues than they spent on peacekeeping missions – clear evidence that armed conflicts continue to boost the global business of killing.

This sad fact is confirmed by the numbers presented last December by the renowned Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), which showed that in 2017 alone, Lockheed Martin, the US-based global market leader, sold weapons worth $44.9 billion. The gap between Lockheed Martin and Boeing, the aircraft manufacturer and number two on the global stage, has now reached $18 billion. The deliveries of F-16 combat aircraft and the Aegis naval combat system, in particular, have fueled the booming business in arms.

For the first time ever, the Russian defense industry was able to displace the United Kingdom and reach the No. 2 spot behind the US. In 2017, the ten largest Russian companies had revenues of $37.7 billion worldwide. In addition to that, SIPRI reported that Russia’s state-owned Almaz-Antey had finally cracked the top ten of the world’s largest armaments companies.

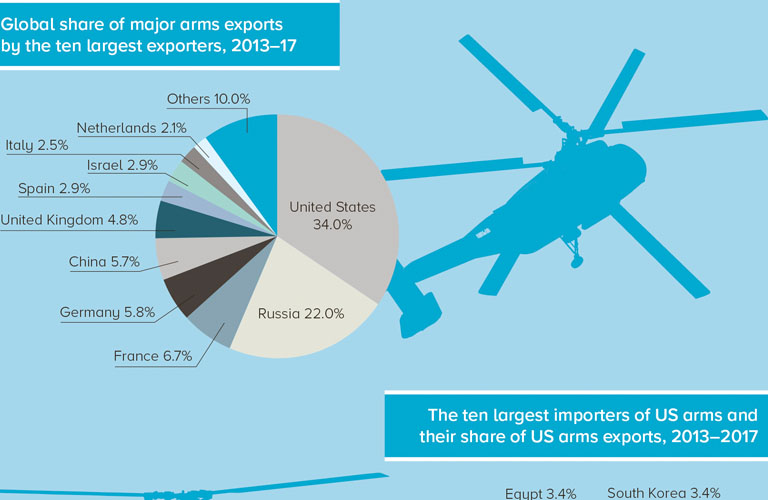

In view of the fact that annual results are subject to fluctuations resulting from the granting of major contracts, SIPRI also measures sales volumes at five-year intervals. In this case, from 2013 to 2017, they recorded an increase in sales of 10 percent over the previous five years. The largest exporters were the US, Russia, France, Germany and China; the largest importers were India, Saudi Arabia, Egypt, the United Arab Emirates and China which, combined, accounted for 35 percent of all global imports.

In terms of the highest-performing companies, the US still leads with industry giants such as Lockheed Martin, Boeing, Northrop Grumman and General Dynamics. Only three of the ten largest global companies are headquartered in Europe. Next to Russian companies, the only other Asian company among the top 30 is Mitsubishi Heavy Industries from Japan; on the bottom half of the Top 100, one finds companies from Singapore and South Korea. Israel has counted among the world’s 15 largest weapons exporting countries for decades.

Pushed out of its second place on the world market by Russia, the UK was nevertheless able to maintain its status as the top producer in Western Europe, with $35.7 billion in sales originating from the country’s seven largest companies. The booming business at Rolls-Royce, GKN and BAE Systems, in particular, prompted a 2.3-percent increase in revenue over the same time period in 2016. With sales totaling $22.9 billion, UK market leader BAE Systems maintained its position as the third-largest defense contractor worldwide behind Lockheed Martin and Boeing.

One particular trend has been confirmed for the third year in a row: the lion’s share of the $398.2 billion in global revenue generated by the hundred largest companies continues to come from the US (57 percent) and Western European arms manufacturing giants (23.8 percent); the Russian share is 9.5 percent.

Still, the final piece of the pie is now being fiercely contested. As in the previous year, Turkish and Indian companies are making headway. Indeed, considering Turkey’s economic crisis, its 24-percent growth in sales is quite an achievement, even for defense industry companies. At $7.5 billion, the four largest arms manufacturers in India still account for 1.9 percent of the top 100.

One statistic not taken into account by SIPRI data is the revenue generated by Chinese companies; this is due to the fact that existing data is very difficult to verify. In 2017, the military budget in Beijing was $228 billion – an increase of 110 percent over 2008. On the other hand, the Pentagon, with $610 billion annually, still spends 2.7 times as much. In 2017, roughly 35 percent of global military spending totaling $1.74 trillion was attributable to the US defense budget, with 13 percent to the Chinese defense budget.

The driving force behind these high growth rates are the highrolling importers in Asia, Oceania and the Middle East. For example, in 2017, Saudi Arabia increased its military spending to $69.4 billion, which is 9.2 percent more than the previous year. The Indian government invested $66.3 billion in that country’s military industrial complex, which is roughly 5.5 percent more than the year before. SIPRI researcher Nan Tian also discerned a “clear trend away from the Euro-Atlantic region.”

Roughly 49 percent of US weapons continues to go to the Middle East. Saudi Arabia alone accounted for the purchase of 18 percent of US armaments between 2013 and 2017 – an increase of 448 percent over the period between 2008 and 2012. Even though the Saudi royal family is expanding its cooperation with the Russian defense industry, deliveries from the US between 2013 and 2017 made up almost two-thirds of Saudi imports, with 23 percent coming from the UK. However, unlike in the 1990s, when Saudi Arabia was the world’s second-largest importer, the Gulf Kingdom is now actually using its weapons – not least in Yemen.

There are also significant exports going from the US to the United Arab Emirates (7.4 percent of total US sales) and Egypt (3.4 percent). Both states are members of the Arab military coalition against the Houthi insurgency in Yemen. Attempts by US congressmen to suspend exports to Saudi Arabia failed in late 2018. For its part, the European Parliament called on EU governments to stop exporting to Saudi Arabia as early as 2015.

And yet, the resolutions coming out of Brussels are not worth the paper they’re printed on. For example, the export ban imposed on Egypt in 2013 did not prevent France from replacing the US as the largest arms exporter to that country. From 2013 to 2017, roughly 37 percent of all Egyptian weapons imports came from France, with 26 percent from the US and 21 percent from Russia.

MARKUS BICKEL

is editor in chief of the German-language Amnesty Journal