How can India raise the costs of Pakistan’s troubling actions towards its neighbor?

Following the terrorist attack in Uri in September of last year, Indian commentators, in understandable outrage, suggested a number of rather dramatic courses of action against Pakistan. These ranged from “surgical strikes” against terrorist training camps in Pakistan Occupied Kashmir (POK) or even at Muridke, near Lahore, to the abrogation of the Indus Waters Treaty, with hopes of bringing the Pakistani economy to its knees.

However, the unpalatable truth is that, while India has a number of diplomatic, economic and military options, most of the feasible ones have been tried before, most notably in the aftermath of the major terrorist attack on Nov. 26, 2008, in Mumbai. The ones that have not been tried — such as reprisals on terrorist bases in Pakistan that exceed the limited cross-border raid in September 2016, which India disingenuously, and misleadingly, referred to as “surgical strikes”— are fraught with major risks, primarily of escalation, and unpredictable consequences. Few realistic and effective retaliatory options remain.

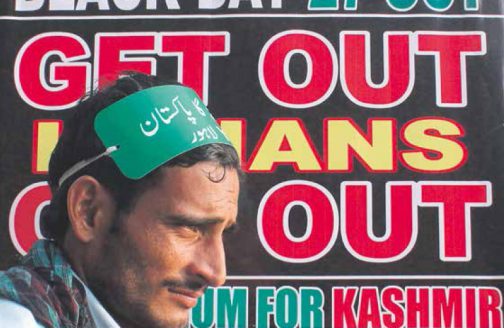

Yet doing nothing is not an option. The idea that malign men in Pakistan can, with impunity, strike Indian targets at will every few months, is galling to most Indians — above all to the hyper-nationalist government of Prime Minister Namenda Modi, which had campaigned using rhetoric extolling a robust response to Pakistani provocation.

India must find a way of raising the costs of such behavior for Pakistan, in the hope of discouraging Islamabad from repeating its actions.

In a speech at a conclave of his party’s leaders in September 2016, the prime minister threatened to isolate Pakistan as a state that exports terror into the world. This is precisely what New Delhi did when the killers from Pakistan took 166 lives in Mumbai on Nov. 26, 2008, although the isolation (and the accompanying diplomatic pressure on Islamabad) inevitably wore off in a few years.

Pakistan is manifestly unwilling or unable to control the terrorism emanating from its own territory. This time, however, isolation poses a bigger challenge for New Delhi for three reasons: 1) Uri claimed fewer victims than Mumbai; 2) they were soldiers, not civilians as in 2008; and 3) various countries have bilateral reasons not to isolate Pakistan.

The US needs Pakistan because of Afghanistan, while China has major strategic interests there, in particular a $46 billion economic corridor comprising China’s largest international development project. As long as major powers continue engagement with Pakistan, while overlooking its wrongdoings, diplomatic isolation will have its limitations.

Airstrikes may seem superficially attractive, not least because they offer the possibility of gratification without commitment. A fighter jet flies from a great height, drops a few bombs, hits a few tents and minor targets and comes back home without further escalation, leaving the victims to contemplate the smoking ruins. On the other hand, limited surgical strikes have a disconcerting habit of remaining neither as limited nor as surgical as their proponents would like. What happens when a plane is shot down in the process? What about Pakistani retaliation, which is sure to be swift and perhaps disproportionate? At what point do you stop the punishment that will inevitably provoke more reprisals? And what about the international opprobrium incurred for breaching the Line of Control or, worse, an international frontier?

Above all, what about the ancillary risks of further escalation? India’s overriding priority is economic development, which requires foreign investment and a peaceful climate for economic growth. Investors do not like to do business in war zones. Can India afford to drive away the funds it needs to pull its people out of poverty?

The possibility of India revisiting the Indus Waters Treaty it signed with Pakistan in 1960 has also aroused some strategists. The treaty gives India control over three eastern rivers — the Beas, Ravi and Sutlej — and Pakistan the western rivers of the Chenab and Jhelum. Vikas Swarup, spokesperson for the ministry of external affairs, hinted that it might be in jeopardy: “For any such treaty to work, it is important that there must be mutual trust and cooperation between both sides. It cannot be a one-sided affair.”

But the treaty under which the waters of the Indus and its five tributaries are distributed between the two countries is not purely a bilateral affair; it was brokered by the World Bank, whose involvement will be automatically triggered if India abrogates it unilaterally. The idea that India, as the upstream country, can stop the flow of water to 65 percent of Pakistan’s geographical area, including the entire Punjab province, creating drought and famine, and generally bringing Pakistan to its knees, must always be considered alongside the swift international condemnation that will follow the moment India begins to initiate such an action.

Moreover, such a maneuver would be more complicated than simply turning off a tap; various measures would be required to ensure that Indian cities are not flooded with the water that is no longer flowing to Pakistan. We would also be setting a precedent we would be loath to see China follow on the Brahmaputra, where it is we who are downstream. We have long been a model state in our respect for international law, and our adherence to morality in foreign policy has survived four wars and a unanimous resolution of the Jammu and Kashmir Assembly calling for its dismissal.

Under the existing treaty provisions, however, India is entitled to make use of the waters of the western rivers for irrigation, storage and even the generation of electricity, provided it is done in a “non-consumptive” manner that does not reduce the ultimate flow to Pakistan. Oddly enough, we have never taken advantage of these provisions, in contrast to what the Chinese claim to be doing with their frenetic dam building on the upper reaches of the Brahmaputra, upstream from India. If we were simply to exercise our rights allowed under the treaty — we are entitled to store up to 3.6 million acre-feet in the western rivers — it would be a more effective signal to Pakistan than any arch statement.

So what can we do? Using artillery to destroy Pakistani forward posts along the Line of Control, preferably the ones near Uri, which must have facilitated the infiltration, is a low-risk option. Although it will certainly provoke some retaliatory shelling, it would probably be containable provided we resist overreaction. And there is always the fantasy depicted in the Bollywood film Phantom – the targeted assassination of jihadist leaders by shadowy covert operatives, amid total deniability by India. This would be sure to cause hesitation in those who dispatch terrorists.

In place of all the blustery demands for bombing and the scrapping of treaties, diligent and responsible action at home is what we need most of all from our government. But the next time Pakistan orders or condones another terrorist assault in India, I, for one, would not like to predict how New Delhi might respond.

A version of this article appeared in print in February, 2017, with the headline “Borderline”.

Shashi Tharoor is the chairman of the Parliamentary External Affairs Committee of the Indian parliament and a former union minister. He is a former undersecretary general at the UN and an award-winning author.