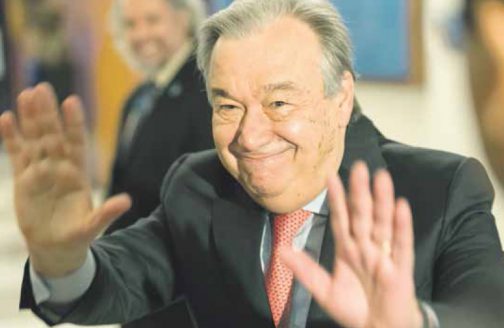

The UN’s António Guterres plans to respond to critical situations before they become crises

The world is “at war,” said António Guterres in 2015; but 2017 should be “a year of peace.” The nations of the world seem to be losing their way amid raging egoism, but Guterres, at he was sworn in as secretary general of the United Nations on Jan. 1 of this year, recalled the original mandate of the UN: “to prevent war by binding all members in a rules-based international order.” The UN is confronting skepticism about its ultimate lack of clout; some see the organization as a paper tiger, but Guterres wants to restore the doubters’ faith in the effectiveness of the institution that turns 72 years old this October.

At the Security Council’s open debate in New York at the beginning of January, he outlined how he planned to achieve this. The UN must no longer just respond to conflicts. “We must rebalance our approach to peace and security.” More than before it must dedicate itself to the prevention of conflicts that “are fuelled by competition for power and resources, inequality, marginalization and exclusion, poor governance, weak institutions, sectarian divides,” and are “exacerbated by climate change, population growth and the globalization of crime and terrorism.”

Guterres feels that as of late “too many prevention opportunities have been lost because member states mistrusted each other’s motives, and because of concerns over national sovereignty.” The result: “We spend far more time and resources responding to crises rather than preventing them.”

People and states are paying too high a price, Guterres said, which is why “we need a whole new approach.” A newly established executive committee should “increase our capacity to integrate all pillars of the United Nations under a common vision for action.” He wants to “launch an initiative to enhance our mediation capacity, both at United Nations headquarters and in the field, and to support regional and national mediation efforts.”

But how can such an endeavor succeed among 193 member states with almost as many varying interests? During his ten years as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), Guterres must have seen that the number of refugees rises in direct correlation to the number and severity of armed conflicts. One year ago he made an unambiguous statement: The EU has failed in its acceptance of refugees. Although Guterres has advocated for a vast global program for the distribution of refugees, success has yet to materialize.

In wars like the one in Syria, many combatants relate to one another almost indecipherably, and UN special envoy Staffan de Mistura has not managed to compel them to sit down at the negotiating table. And what if one of the five permanent members of the Security Council cripples the UN through veto, or simply acts unilaterally as Russia has recently done in Syria? And what would the new UN chief do if small countries feel threatened by larger ones?

Guterres would then try to act as “world moderator” (Franklin D. Roosevelt), with a soft voice and a “diplomacy for peace”; he sees himself as a bridge builder, who must try to understand the positions and arguments of all sides of any conflict. He is considered to be an excellent speaker with the power to convince, as well as someone who can broker compromise.

And what does Guterres say to Vladimir Putin’s American counterpart, when he disparages the UN as a “just a club for people to get together, talk and have a good time”? Guterres responded like an Aikido master, arguing that preventive action can be achieved “only through reasoned discussion, based on facts and the pursuit of truth.”

And finally, what if the new US president meddles with the UN’s greatest achievement in recent years, the climate change tenets formalized in the Paris Agreement and ratified by the US? Guterres appealed to rationality: “Tackling climate change will help prevent global conflict.” And that – perhaps an argument for utilitarian dealmakers – can cut costs.

Guterres, once prime minister of Portugal, is the first former head of state to lead the UN. He is considered to be a straight talker, and someone expected to confront the world’s political leaders on equal terms. He has already visited Putin, as well as President Xi Jinping of China. Guterres will also restructure the 44,000-strong organization, as he has identified some shortcomings: the UN response to crises “remains fragmented.” He is requesting “changes to our culture, strategy, structures and operations.” The new Executive Committee should ensure that all pillars of the UN work together toward a “common vision for action.” If Guterres succeeds in requiring at least two members of the Security Council to carry out a veto, the man at the top of the UN would once again be more of a general than a secretary.

A version of this article appeared in print in February, 2017, with the headline “New diplomat in town”.