Trump’s arrival in the White House has put the worsening US-Russian confrontation on hold, for now

What a difference a year makes. In early 2016, a lot of Europeans saw Russia as the most serious threat to their security. Nowadays, quite a few of them are torn between identifying Russian President Vladimir Putin or US President Donald Trump as the bigger challenge. After 70 years of entrusting their foreign and security policy to Washington, Europe is realizing that unless it finds an international identity of its own and becomes an actor on the world stage, it will be irrelevant both politically and strategically. This is no small task.

Meanwhile, the United States under the Trump administration is moving from being unpredictable to becoming potentially unstable, as the conflict between the 45th president and the opposition to his rule spreads beyond the political class and re-energizes activists on both sides of the spectrum, further dividing an already polarized US. A conflict on such a scale would undoubtedly have an impact on US foreign policy and lead to even more instability at the global level. It is hard to predict with any certainty where Trump and the US will be one year from now, which renders moot assumptions concerning just about everything else.

Trump is not a Kremlin man – even if one accepts all the allegations about the DNC hacking, the infamous kompromat and all the evidence about the actual use of the stolen secrets by the Russian propaganda apparatus. However, the scale and intensity of the scandal about Trump’s purported dependence on Putin reveal a lack of selfconfidence among American elites the likes of which have not been seen for decades. America’s founding myth of exceptionalism is suddenly in danger of unraveling.

This is serious. Big countries like the US, China or Russia are virtually invincible if attacked from the outside, but they can become brittle if their domestic systems and self-images become delegitimized.

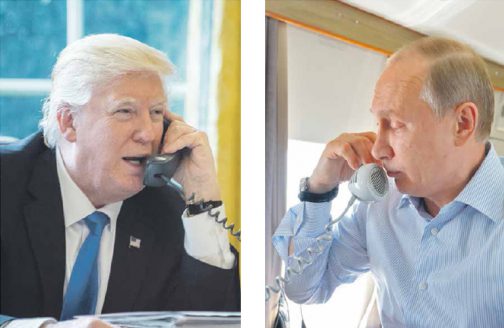

We are not there yet. The US can overcome its current crisis and safely transition over time from global dominance to global pre-eminence. There are even some bright spots. With Trump’s arrival in the White House, the worsening US-Russian confrontation has been put on hold. This ceasefire may not last long, and there is no guarantee that the conflict will not resume, in perhaps an even sharper form. However, while the likelihood of a kinetic collision between Russian and American military aircraft or naval ships had risen ever higher during Barack Obama’s last two years in office, a trajectory sure to have continued under Hillary Clinton, this risk has now markedly decreased.

As Trump and Putin are transactional politicians, they may indeed speak the same language of Realpolitik. Yet it does not follow that even if they understand each other perfectly, they will be able to make deals.

Trump is clearly focused on containing China and destroying Islamic terrorism. For Putin, however, there is no question of siding with Washington against Beijing, with whom Moscow has built a solid relationship over the past 30 years. This relationship will not break unless China embarks on an adversarial course against Russia – a highly unlikely eventuality in the foreseeable future. The Washington- Beijing-Moscow triangle is back in play, but the US is far from being its main player.

Russia would certainly welcome the possibility of joint military action with the Pentagon against the Islamic State (IS) in Syria. A military coalition of equals would add to Moscow’s prestige and put Russia’s conventional forces on par with America’s in that war. US support for the Russia-led political settlement in Syria would also be welcome in Moscow. Russia, however, is unlikely to perform heavy-duty tasks for the US in the Middle East. It will follow its own strategy there, geared toward its own goals. With regard to Iran, to cite but one example, Putin’s calculus and objectives differ a great deal from Trump’s.

Ahead of Putin’s first face-to-face meeting with Trump, the Kremlin has been closely watching the first steps of the new US administration. Russia’s hope is to establish a durable co-equal relationship with the new president, one built on a balance of the two countries’ national interests.

The concern in Moscow, however, is that the bipartisan anti-Russian consensus in the US has shown no signs of subsiding since Trump’s inauguration. It is still true, for example, that if Trump were to lift the Russia sanctions by executive order, Congress would soon reinstate them as law, making them virtually impossible to remove. Should Washington decide to begin supplying lethal arms to Kiev, which, according to Rex Tillerson, would have been preferable to sanctions in 2014, the US-Russian relationship would immediately return to the danger zone.

Even if this does not happen, the crisis in Ukraine, now in its fourth year, will probably continue unresolved. The Minsk agreement cannot be implemented, as this would be tantamount to suicide for the current political regime in Kiev. Nor is there any real appetite for this in Donetsk and Lugansk, yet Donbass remains under Moscow’s tutelage and would ultimately do Russia’s bidding. For the Kremlin, the Minsk accord promises a de facto neutral Ukraine with a pro-Russian element legitimized and protected within it. Even though it is hard to expect the White House to align itself with the Kremlin on this matter, the mere specter of a Trump-Putin deal on Ukraine led to a spike of violence in Donbass in early February 2017.

If there is no deal, the conflict will remain unresolved, but not safely frozen and isolated. The shelling of Donetsk has provoked renewed calls in Russia to solve the Ukraine problem by force. At this stage, these calls can probably be chalked up to psychological warfare, but an escalation of the conflict is unfortunately more probable than its resolution.

Putin and Trump may meet in Finland this spring, but a Helsinki 2 remains out of reach – as well as a new Yalta. Going forward, Europe will be neither managed nor divided between America and Russia; it will remain in flux.

It is time for Europeans themselves, above all the French and the Germans, to begin thinking seriously about the EU’s own security. In addition to Ukraine, it is the Balkans that should command Europe’s attention. Even though Russia now regards the region as falling within the EU’s sphere of influence, local tensions – two decades after the end of the post-Yugoslav wars – have not been put to rest. It is also an area where a deadly combination of criminality, radicalism and religious extremism poses a direct threat to the EU.

For starters, European leaders need to admit that countries outside the European Union operate on different principles than those that prevail within the EU, and then act accordingly. Europeans need to rediscover geopolitics and learn the game of statecraft. Yet they can only succeed if they have the will to make decisions about war and peace, crisis management and conflict resolution, and back these up with diplomatic, economic and military power. If they fail, the consequences will be dire. As for Trump, for Europe he may be a blessing in disguise – one that can help Europeans find a role of their own in a world that has gone unstuck.

A version of this article appeared in print in February, 2017, with the headline “With friends like these…”.

Dmitri Trenin is director of the Carnegie Moscow Center and an author. His most recent book is Should We Fear Russia? (Polity: Cambridge, 2017).