With or without you

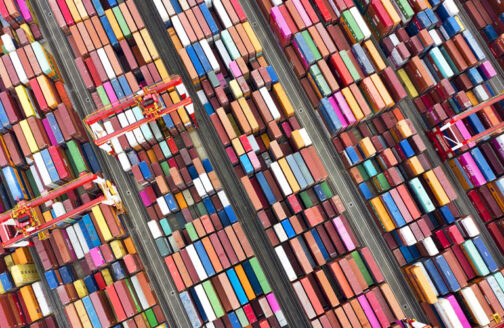

Contain your enthusiasm: Yangshan deep water port terminal, Shanghai, China.

Contain your enthusiasm: Yangshan deep water port terminal, Shanghai, China.

Credit: picture alliance / Finn / Costfoto

The world is at a turning point. Or so they say

A growing chorus of analysts, investors and policymakers claim that much like World War I and the 1918 influenza pandemic brought an end to the first great era of globalization, the combination of Russia’s war in Ukraine, Covid-19, simmering populism and geopolitical competition between the United States and China – or, as historian Adam Tooze calls it, the “polycrisis” – is kicking the current era of globalization into reverse. So-called “deglobalization” has been a theme of many recent op-eds, academic debates, shareholder letters and high-level conferences.

Yet globalization has been pronounced dead many times before: after the global financial crisis in 2008, after the Brexit referendum in 2016 and the election of Donald Trump later that year, and after the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020. Clearly, the trajectory of globalization is wildly overdetermined. That none of these predictions have come to pass should give people pause about predicting deglobalization once more.

In fairness, those proclaiming the demise of globalization as we once knew it are not totally wrong. It is true that the era of “hyperglobalization” that lasted from the 1970s to the 2008 global financial crisis, during which a hegemonic US drove a top-down process of trade liberalization and global integration, is now dead and buried along with globalism, the ideology that propelled it, and unipolarity, the international order that upheld it.

But rather than the end of economic integration, the world is experiencing a geopolitical recession that has left globalization drifting, bereft of drivers and champions, of rule makers and enforcers.

A more inward-looking US no longer has the political will to serve as architect and guarantor of the world economy. China, meanwhile, is beset with structural economic challenges that limit its ability to promote its own order. And no other country or group of countries has the capacity to fill the void.

That does not mean that globalization is ending. Such an outcome would require the US to actively turn against economic integration. Bombast aside, that did not happen under Trump, and it is not happening under US President Joe Biden. Rather, the US has simply stopped leading the drive for ever-greater globalization. This leadership vacuum that characterizes the geopolitical recession has resulted in the fraying of the “governance of globalization,” as the former World Bank President Robert Zoellick has put it. But globalization itself is not fraying – it is simply adrift.

A look at economic data belies the notion that globalization is reversing. Even as global capital flows relative to GDP have moderated since their peak in the middle of the first decade of this century, cross-border investment has continued to grow. Worldwide merchandise trade is near all-time highs, having already surpassed pre-pandemic projections. Multilateral trade negotiations have stalled, but the number of regional trade agreements in force has grown continuously since the 1990s, more than doubling since 2008.

Trade in goods has slowed relative to global output since 2008, but this shift does not signal deglobalization. On the contrary, the plateauing of the global trade ratio is partly a side effect of economic development – a sign of globalization’s success. Take the example of China, which has seen its ratio of trade to GDP decline by nearly 30 percent since 2006 and which, by virtue of its size, has been the biggest contributor to the slowing worldwide trade-to-GDP ratio. As the country has grown richer and its economy more complex – owing to market reforms and integration into global markets – China’s growth model has shifted away from exports and toward domestic consumption and investment. At the same time, domestic demand has shifted away from goods and toward services, which are traditionally less tradable. China has also moved up the value chain, manufacturing fewer cheap consumer goods and more advanced intermediate inputs, and now produces a greater share of the value of its exports domestically.

None of these trends constitutes disintegration or retrenchment. Rather, they reflect the fact that globalization has diminishing returns, and not just for China. Now that most countries are already relatively well integrated into the global economy, the world as a whole has less to gain from additional globalization. This shows up in the data as a decline in global trade intensity, but it is a sign of progress, not of deglobalization.

What is more, technological advances such as e-commerce, automation, artificial intelligence, robotics, cloud computing and telework have transformed many labor-intensive production processes into capital- and knowledge-intensive processes. Trade designed to take advantage of labor-cost differentials between countries has consequently declined worldwide – but not because of any conscious turn against globalization.

The growing importance of services and intangibles in the modern economy has also fueled the false impression of deglobalization. Trade in services and intangibles has been accelerating for 15 years and accounts for an increasingly large share of global economic activity. This is especially true of trade in digital services. For instance, computer and communication services now make up around half of all services exports and three percent of global GDP. Intangibles such as research and development, intellectual property rights, branding, design, and software have also grown significantly as a share of total trade, investment, and output. Yet many services and intangibles are not captured by current trade data.

All this suggests that traditional measures of globalization are being rendered obsolete. In reality, the world is more interconnected than ever. And interconnection begets interconnection, because the more interconnected nations grow, the harder and costlier it becomes for them to decouple.

To be sure, parts of the world are decoupling, but only some parts and only to some extent.

Advanced industrial democracies are forcibly decoupling from Russia in a way that is near total and likely permanent. This decoupling will have dire implications for Russia’s economic, military and geopolitical standing.

But Russia is hardly being cut off from the entire world. China and India have already increased their purchases of Russian oil from a combined 1.7 million barrels per day in June 2021 to nearly 3 million barrels per day in December 2022, and at a discount. Developing countries still rely on Russian grain and fertilizer, and many regular and irregular armies continue to use Russian weapons and mercenaries. Much of the world will continue to do business with Russia.

The US and China, meanwhile, are locked in an intensifying geopolitical competition that has led them to decouple in areas perceived to be of national security importance. These areas encompass an ever-growing number of “strategic” sectors – most notably semiconductors but also other dual-use technologies such as renewable energy and social media platforms – that are now off-limits for foreign trade and investment.

Yet this decoupling can only go so far because the US and Chinese economies are so interdependent that a full divorce would be ruinous for both countries and for the world. The US is still China’s largest goods trading partner and export market, and China is still the largest goods trading partner of the US, its largest supplier of imported goods, and its third-largest export market. The US and Chinese business communities want to do more, not less, business with each other. Likewise, most other countries – including the closest US allies in Asia and Europe, which are just as wary of China’s rise – have no interest in mutually (and globally) assured economic destruction and are ramping up investment in and exposure to both the US and Chinese economies.

But even though the partial decoupling of Russia and the West and China and the US does not amount to deglobalization, it does indicate a shift in the nature of globalization. The global economic order is becoming more multipolar and fragmented in the absence of international leadership. Whether we like it or not, geopolitics will increasingly creep into economic calculations. Countries and companies will attempt to make themselves more resilient to external shocks and insulate themselves from geoeconomic pressures through a combination of “ally shoring,” “nearshoring,” diversifying supply sources and stockpiling. It is even possible that cross-border economic activity will splinter into geopolitical spheres of influence, as countries deepen their integration with friends and reduce their reliance on foes.

These trends point away from the aggressive globalization of recent decades, but not toward autarky. Globalization is too hard to kill: the inertia is too strong, the benefits of scale and specialization too great and the costs of reversing globalization too high. The global value chains that produce most modern goods are so complex and spread out that recreating them at a national level is virtually impossible. Western companies will increasingly pull back from China, no doubt, but for the most part they won’t bring production back home, instead shifting it to friendly, lower-wage nations such as Mexico and Vietnam. With few exceptions, reshoring and insourcing would prove excessively costly – and risky. As the shortage of baby formula in the US demonstrated last year, resilience is best achieved through diversification and spare capacity – not self-reliance.

The shifts in the pattern of global integration may well result in efficiency losses. Politics and geopolitics, after all, increase transaction costs and impede the optimal allocation of resources. Global integration will no doubt be less coordinated, deliberate and efficient than before. But it will still be in most countries’ interest given how much worse the alternatives are.

Globalization may be getting a makeover, but it isn’t going anywhere.

This article is adapted from “Globalization Isn’t Dead: The World Is More Fragmented, but Interdependence Still Rules,” originally published in Foreign Affairs, with additional modifications made by the author.

Ian Bremmer is president and founder of Eurasia Group.